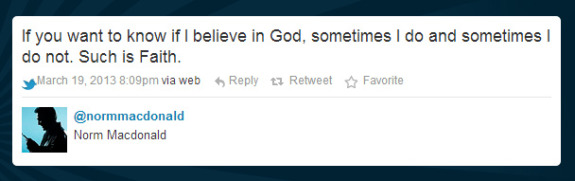

Earlier in the week, Norm MacDonald went on one of his familiar, lengthy Twitter sprees. These are binges of tweets and retweets — usually about golf, sometimes even attempts at literary fiction — and they're great. If you have any affection for his style of sincerity and unpredictability, this look at Norm amusing himself 140 characters at a time is a golden dream. Earlier this week was different. A golfer had mentioned scripture, someone reacted angrily, and Norm aired his concern about that reaction.

If you were online when it happened, you would have seen hundreds of retweets by Norm and his responses to them one by one. A lot of people don't know this, but Norm MacDonald is a pretty devoted to studying scripture. He spoke about it on his episode of WTF with Marc Maron (the only podcast episode I've gone back to relisten to):

I've been struggling with faith, I'll just throw myself into religion sometimes. The problem with that is you get into churches and stuff, and then you get into men and stuff like that. It's very easy to fall into the trap, "God's bad because this priest fucked a kid," which is retarded, why's that mean God's bad? If you go to any church, obviously it's led by fallible men,and you can't believe in them, so you've got to come to it yourself somehow. But I don't have the answer of how you do that or anything.

He seems to be religious in the way the great Russian authors were religious, and skeptical of people who have things figured out. The problem is, in the context of modern day America, and especially on Twitter, siding with religion is a highly loaded political position. The voice of religion has been co-opted by the loudest on the right, while the left's loudest have been very willing to cede that ground.

The outrage online was predictable. Many were disappointed at Norm, some were angry at him, several challenged him on the grounds of "what about dinosaurs??????" and other incisive gotchas. There were those who supported him, declaring that believers were oppressed in today's America. When it got to the more ethical criticisms, such as the church's association with pedophile priests or its stance on homosexuality, Norm's responses were pretty mainstream: pedophilia is a problem with man, not with scripture, and the stereotype to which we hold men of the cloth is unfair when most work very hard for little pay, and other professions are just as infected but not held to such judgment. On treatment of gays, Norm's response was along the lines of, "Says who?" and found it irrelevant to his understanding. In his response, the bible was a way to salvation, not a rulebook on how to live.

But none of that really mattered. The narrative set up is that religion is conservative and bigoted while athiesm is science. Norm wondered aloud if being religious was simply "not stylish" and he's partially wrong — it's still very much the overarching majority; the priveleged, mainstream position. It's just in his circle of stand-up comedy and SNL nostalgists that it's not particularly fashionable. Norm lives in a counterculture, and his adoption of a mainstream faith, to some, is at odds with that.

I'm sure some of it is the signal to noise ratio. I don't know if most of the responses he received were volatile, but I do know that the internet is a constantly volatile place. There is almost nothing you can say that wouldn't generate a trollish, hateful response from someone hiding behind the benefit of anonymity. Still, I don't believe it to be an inaccurate picture of the popular standing of religion and how it is understood.

When I found out Norm was deeply invested in understand religion, I was glad. He has always been one of my favorite comedians, and to find out that he was sensitive to this stuff made him even more relatable. Religions need better spokespeople. They need better role models and figureheads and celebrity endorsements that portray an alternate way to adopt a faith, away from those that hold megaphones in our politics and our megachurches. I'm not suggesting PR campaigns and billboards — just knowing that a complex, personable version exists is enough for some people.

A lot of the way I deal with religion — and fear of death, the chaos of the universe and inherent kindness/evil in all of us — has been shaped by the better role models I was lucky enough to find. People like the great authors of literary fiction, or artists like Sufjan Stevens and, now, Norm MacDonald. The difference in how they talk about faith is this: it's personal, emotional, and has more questions than answers. Something so enormous ought to be this nuanced.

"Casimir Pulaski Day" by Sufjan Stevens was a big one for me. The song is about two young kids in love, one suddenly diagnosed with bone cancer, and the fallout of the tragedy. It's one of his most famous songs, behind only "Chicago," and for me it was always about the lines where the speaker's religion gets tangled with his ineffective reality:

Tuesday night at the bible study, we lift our hands and pray over your body but

nothing ever happens.

Oh the glory that the lord has made, and the complications when I see his face

In the morning in the window

All the glory when he took our place, and he took my shoulders and he shook my face

And he takes and he takes and he takes.

Then the song ends. In the drab Christian Rock genre, the song would be sure to wheel back around to optimism and unwavering faith and strength in the face of hardship, but that's not life. It leaves no room for questions or doubt. It doesn't accurately convey how absolutely disappointing religion can be. Most importantly, disappointment doesn't invalidate god — it's simply part of the experience. "Casimir Pulaski Day" is an image of a god that sometimes just takes, and we all figure out our own way to justify it, rationalize it, or rebel against it.

The scientific accuracy of miracles, the rules about what genitals go where and when, the sins of men in church roles of authority can really be ancillary stuff outside of religion, if you wanted it to be. Of course, these arguments will always be present because the people with the power to steer our cultural conversation won't ever see it that way, but who cares about them? Who cares about the loudest outliers among us?

Progressives often posit that the regressive teachings of the church will be its eventual end. If this "unfashionability" takes deeper root, yeah, I can see that happening. You can only resist modernism for so long. If we're concerned about the regression, we also have a responsibility to raise up the progressive alternatives that arise. When people with better access to the cultural conversation, people with megaphones, offer us a different way of living with religion that doesn't exclude or oppress or demand, then we should take that up. Who wouldn't want to live in a world of religion based on love, philosophy and salvation over fear, rules and uniformity?

I haven't been to church in a long time. Doubt, personal adaptation, laziness — there are a lot of reasons I could give. In times of dire need and uncertainty, I have woken up on early Sunday mornings just to spend one admittedly superstitious hour in a pew. I never used to do that before. It didn't really matter to me if I was really beaming up a message to an unknowable entity in the sky. It was more about the ritual than the supernatural appeal. As a brash High School freshman atheist, I might have called this weakness. Today, I think that weakness is human, and sometimes beautiful, in the way that it draws us closer to empathy. When I kneel at a pew, it's to quell a storm in my mind. Regardless of its validity, I was glad to have it as an option.